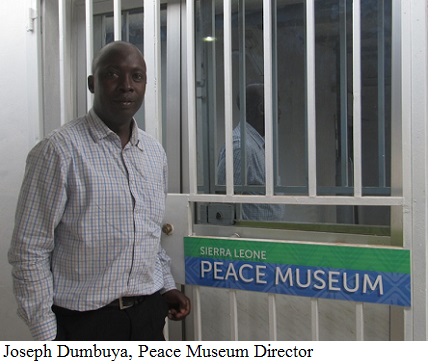

Joseph Dumbuya stands in the main room of Sierra Leone’s brand-new Peace Museum, surveying a large canvas painting of a war amputee and the blank space next to it, to be curated over the coming months. “We have to invest in peace,” he tells me. Dumbuya is the Peace Museum’s Director, and faces, in addition to the usual resource shortages that plague projects like this one in the Global South, a societal culture of silence about the civil war. People ask him why they need the museum when it will just open old wounds – they tell him, “isn’t it better to look forward and not back?” Many post-conflict countries grapple with the balance between remembering and forgetting atrocities, but in Sierra Leone, thus far, forgetting dominates. The Peace Museum’s creation challenges this notion that the best way to deal with trauma is to act like it doesn’t exist.

Joseph Dumbuya stands in the main room of Sierra Leone’s brand-new Peace Museum, surveying a large canvas painting of a war amputee and the blank space next to it, to be curated over the coming months. “We have to invest in peace,” he tells me. Dumbuya is the Peace Museum’s Director, and faces, in addition to the usual resource shortages that plague projects like this one in the Global South, a societal culture of silence about the civil war. People ask him why they need the museum when it will just open old wounds – they tell him, “isn’t it better to look forward and not back?” Many post-conflict countries grapple with the balance between remembering and forgetting atrocities, but in Sierra Leone, thus far, forgetting dominates. The Peace Museum’s creation challenges this notion that the best way to deal with trauma is to act like it doesn’t exist.

Sierra Leone is a small West African country, with a population of 5.7 million, bordering Liberia, Guinea, and a stretch of Atlantic coast. From 1991 to 2002, it was consumed by a civil war notorious for its brutality, with widespread sexual violence, recruitment of child soldiers, and amputation used as a fear tactic. Fueled in part by rebel groups spilling across the border from Liberia’s civil war, driving factors of the conflict in Sierra Leone included power struggles over control of diamond revenues, social unrest over unequal access to inadequate resources such as education, water, sanitation, and electricity, and youth disenfranchisement. None of these conflict factors have yet been resolved and remain as major issues shaping social and political life in the country. Though theoretically the government is a constitutional democracy, in practice, it is less than democratic. The current ruling party is the All People’s Congress (APC) led by Ernest Bai Koroma, and the main opposition, the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), has traded power with APC throughout the war and postwar period.

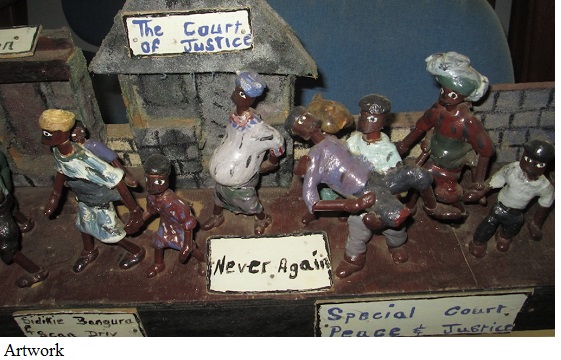

The Peace Museum came about as Sierra Leone’s latest attempt to address the legacy of the civil war as the Special Court of Sierra Leone, created to try war criminals, closed its doors on December 2, 2013. The Lomé Peace Accords ending Sierra Leone’s decade-long civil war were signed on July 7, 1999, and throughout the 2000s, the Special Court convicted nine people over the last decade, with the most notorious warlord, Charles Taylor, moved to The Hague to finish out his trial.

Occupying the old security building of the Special Court, the Museum and Court both address the violence that Sierra Leoneans experienced and how that violence can be dealt with by institutions and society. The Special Court of Sierra Leone attempted to strengthen the rule of law and to promote post-conflict reconstruction, in addition to justice for those most responsible for the atrocities. There was also a Truth and Reconciliation Commission report published to extend this mission, and grassroots organizations have tried to make the Special Court proceedings more tangible to the masses by screening video footage of the trial in rural towns and facilitating discussions about them in town hall meetings throughout the country. As in Cambodia, where much of the population lives outside the capital city where the Court is based, human rights-focused NGOs and government sponsored groups took the lead in distilling elite, legal language into something communities could relate to. In both Cambodia and Sierra Leone, the successes and failures of the Courts and grassroots advocacy projects are hard to measure, but they are necessary ingredients to rebuilding a shattered state and citizenry after war.

The Peace Museum came about as the Special Court commissioned a study on the future uses of the Court site after the Court’s closure. In a country where substantial infrastructure is a scarce commodity – everything from roads to electric lines and plumbing – the physical infrastructure of the Court complex buildings is a luxury – solid walls, air conditioning, and the whole compound fenced in and secured by guards. While the fences and guards might intimidate some visitors, the handoff of the site to the government will make the compound more accessible to the public. A block of buildings in the compound was turned over to the Sierra Leone law school in 2012, and the Special Court building itself will become the domestic Supreme Court. Both the law school and the Peace Museum will further entrench the legacy of the Court in Sierra Leone by repurposing these spaces for projects that contribute to the rule of law and promoting a culture of peace.

The Peace Museum came about as the Special Court commissioned a study on the future uses of the Court site after the Court’s closure. In a country where substantial infrastructure is a scarce commodity – everything from roads to electric lines and plumbing – the physical infrastructure of the Court complex buildings is a luxury – solid walls, air conditioning, and the whole compound fenced in and secured by guards. While the fences and guards might intimidate some visitors, the handoff of the site to the government will make the compound more accessible to the public. A block of buildings in the compound was turned over to the Sierra Leone law school in 2012, and the Special Court building itself will become the domestic Supreme Court. Both the law school and the Peace Museum will further entrench the legacy of the Court in Sierra Leone by repurposing these spaces for projects that contribute to the rule of law and promoting a culture of peace.

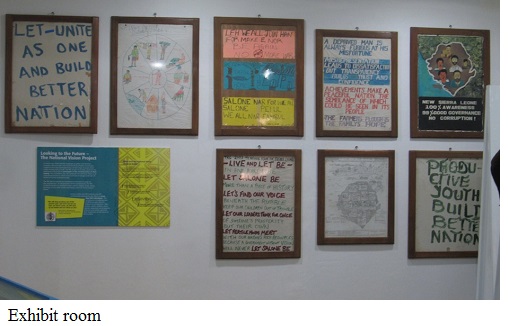

The Peace Museum itself consists of three components: the exhibition rooms, a memorial garden, and an archive. The smaller room into which one enters the museum has already been curated and presents historical documentation about the war and its actors, including amulets and weapons of the civil defense forces, including the Kamajors, a men’s secret society group that believed their charms would deflect bullets. There are hand-painted posters by community members asking for peace, and photographs of war survivors, many of whom had limbs hacked off by rebels. This first room is evocative and polished, the result of Dumbuya’s collaboration with an American exhibit designer from Studio Tectonic, though during the course of my visit a mounted photograph of Charles Taylor fell off the wall twice – basic technical things, like strong adhesive, are still lacking.

The second room is much larger than the first and still bare. Dumbuya has shelves of war-related artifacts donated by Sierra Leoneans that he has collected from throughout the country that need to be sorted and curated. He is also interested in making a child-friendly portion of this second room, with exhibit material that will engage younger people. Informational exhibits must be carefully thought through to allow those who are illiterate, (43 percent of Sierra Leoneans) to learn about the war through art and artifacts: paintings, photos, charms and juju items, weapons, and clothing worn by fighters will all be included. In addition to a video monitor in the first exhibit room, there is space for the second room to house an audiovisual display that could draw in those who struggle with the standard museum-ese.

The second room is much larger than the first and still bare. Dumbuya has shelves of war-related artifacts donated by Sierra Leoneans that he has collected from throughout the country that need to be sorted and curated. He is also interested in making a child-friendly portion of this second room, with exhibit material that will engage younger people. Informational exhibits must be carefully thought through to allow those who are illiterate, (43 percent of Sierra Leoneans) to learn about the war through art and artifacts: paintings, photos, charms and juju items, weapons, and clothing worn by fighters will all be included. In addition to a video monitor in the first exhibit room, there is space for the second room to house an audiovisual display that could draw in those who struggle with the standard museum-ese.

The memorial garden is out back of the exhibit rooms, reached through two doors and a stairway, though there is an alternate disabled access route. I am spat out into the morning heat and across a “peace bridge” traversing a garbage-clogged gulley and linking the exhibition rooms to the memorial garden. Magpies scavenged the plastic water bags and cracker wrappings against a backdrop of green slime as I made my way to the garden, a modest lawn covered with white flagstones leading up to a bamboo framed tent, meant to represent the refugee tents many Sierra Leoneans lived in (and some still live in) once the United Nations intervened to address the human security fallout of the war. The high concrete walls that surround the garden will someday be engraved with the names of the war dead, if funding can be found to pay for it. The memorial garden design was the result of a design competition in 2011, and many of the unsuccessful entries are works of art in their own right, presenting haunting visual references to what war and peace look like to everyday Sierra Leoneans, and why remembering the conflict is so important. Many of these designs will be displayed in the second exhibition room.

While the exhibition halls and the memorial garden will have a high appeal to casual visitors, foreigners and educated locals alike, the third component of the Peace Museum, the archives of the Special Court and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), will have a more specialized user base. The protocol for archival access still needs to be established, as the Peace Museum is merely the custodian for this important collection of documents over which the Human Right Commission of Sierra Leone maintains regulatory control. All public records of the Special Court and TRC are available now in both print and digital copy, while Special Court confidential records remain in the Hague and TRC confidential and restricted access records will be declassified fifty years after publication. In the long run, the association of the archives with the Peace Museum reinforces its status as the central site of war memory in Sierra Leone. Domestic and international researchers have their work cut out for them navigating this newly available body of information, and the rules that regulate it.

While the exhibition halls and the memorial garden will have a high appeal to casual visitors, foreigners and educated locals alike, the third component of the Peace Museum, the archives of the Special Court and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), will have a more specialized user base. The protocol for archival access still needs to be established, as the Peace Museum is merely the custodian for this important collection of documents over which the Human Right Commission of Sierra Leone maintains regulatory control. All public records of the Special Court and TRC are available now in both print and digital copy, while Special Court confidential records remain in the Hague and TRC confidential and restricted access records will be declassified fifty years after publication. In the long run, the association of the archives with the Peace Museum reinforces its status as the central site of war memory in Sierra Leone. Domestic and international researchers have their work cut out for them navigating this newly available body of information, and the rules that regulate it.

The exhibits, memorial garden, and archives in the Peace Museum are poised to serve a critical function in Sierra Leonean society: breaking the culture of silence that surrounds the war. As is the case in the aftermath of violence in so many places, the urge to forget and move on is prevalent in Sierra Leone. However, Sierra Leone’s transition to democracy is by no means secure, and the likelihood of its return to conflict cannot be ignored. Despite millions of dollars in donor aid invested in the post-conflict reconstruction phase, many of the root causes of conflict – inadequate resources such as sanitation, water, and electricity, and unequal access to these resources, poor quality education, and youth disenfranchisement, to name a few – are still prevalent.

The exhibits, memorial garden, and archives in the Peace Museum are poised to serve a critical function in Sierra Leonean society: breaking the culture of silence that surrounds the war. As is the case in the aftermath of violence in so many places, the urge to forget and move on is prevalent in Sierra Leone. However, Sierra Leone’s transition to democracy is by no means secure, and the likelihood of its return to conflict cannot be ignored. Despite millions of dollars in donor aid invested in the post-conflict reconstruction phase, many of the root causes of conflict – inadequate resources such as sanitation, water, and electricity, and unequal access to these resources, poor quality education, and youth disenfranchisement, to name a few – are still prevalent.

Though there have been a few benchmarks of success, like nearly reaching gender parity in primary schools, the future for many Sierra Leoneans seems dire. In this context, the importance of remembering how conflicts escalated into brutal civil war, and why such a path should no longer be an option, remains prescient. Currently, there is no formal education curriculum that teaches schoolchildren about the war. Unless families or community organizations talk about it, children grow up not realizing the history of their country, nor the cost in human life that the war took. To entrench sustainable values of peace, sites of remembrance like the Peace Museum can serve a vital function in addressing this culture of silence.

Please see the following websites for more information:

Peace Museum, http://www.slpeacemuseum.org/

Special Court, http://www.sc-sl.org/

Truth and Reconciliation Commission, http://www.sierraleonetrc.org/

The Peace Museum in Freetown, Sierra Leone is now open to the public. Visitors may come to the security/reception area and ask for the Museum to be opened for them, or contact Joseph Dumbuya at slpeacemuseum@gmail.com for an appointment and personal tour. Please also contact him for more information about the Museum, or to share ideas about fundraising or curating.

Mneesha Gellman lives in Freetown, Sierra Leone, where she researches peacebuilding education and language politics. She has a PhD in Political Science from Northwestern University.